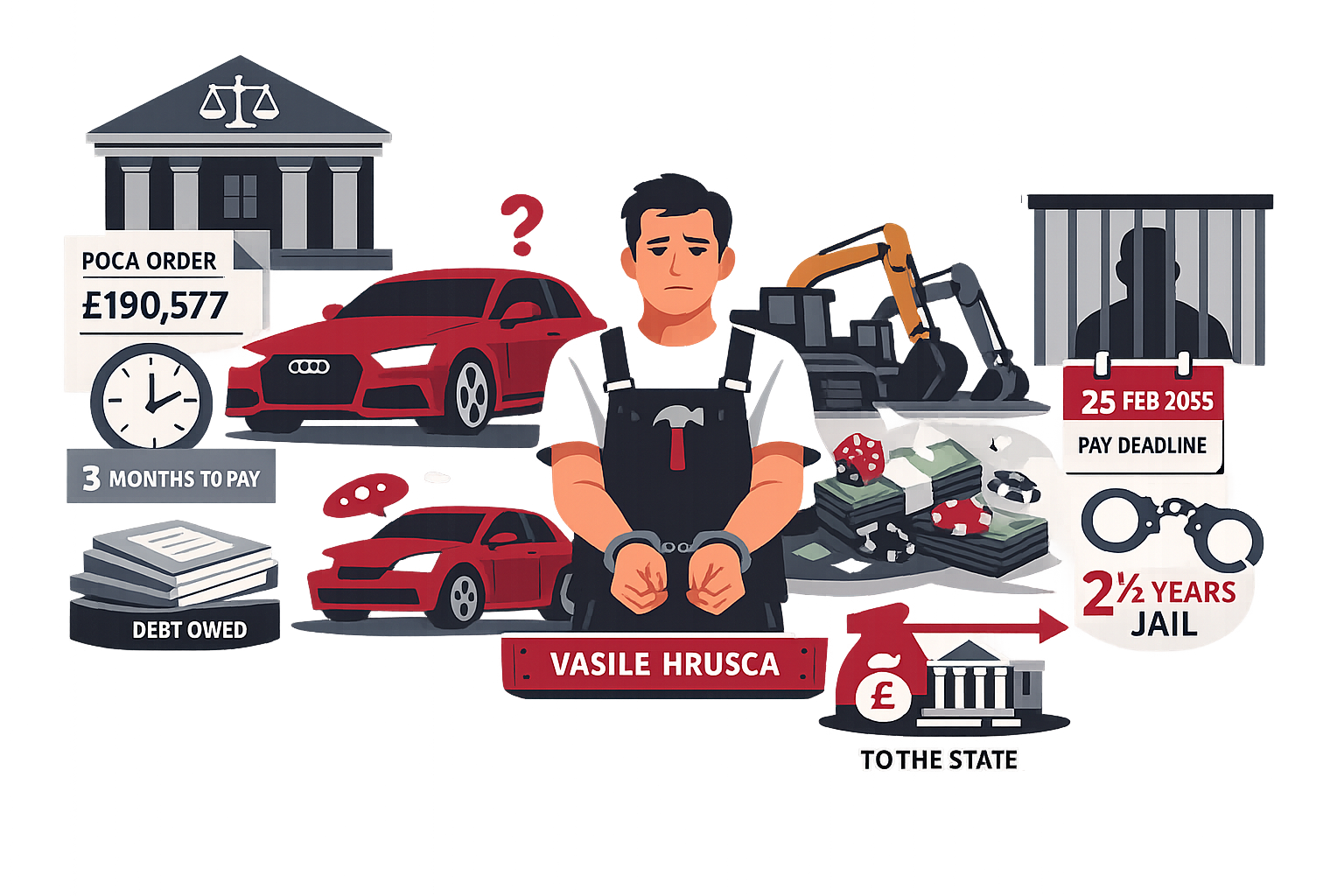

Snaresbrook Crown Court has ordered Hornchurch builder Vasile Hrusca to repay £190,577 within three months under the Proceeds of Crime Act. If he fails to pay, a default term of two-and-a-half years’ imprisonment can be activated and the debt will still be owed. The Insolvency Service set out the order in a release published on 3 December 2025, confirming the confiscation hearing took place on Tuesday 25 November 2025.

This follows Hrusca’s earlier criminal sentence: on Friday 17 January 2025 he received 18 months’ imprisonment, suspended for two years, a four‑year director disqualification, 150 hours’ unpaid work and 15 rehabilitation days after admitting theft and fraudulently removing company property contrary to section 206(1) of the Insolvency Act 1986. Those details were confirmed by the Insolvency Service’s January sentencing notice.

The conduct underpinning the confiscation is stark. In June 2019-three months before liquidators were appointed-Hrusca transferred £67,769 from his company’s account to settle the outstanding balance on a hire purchase agreement for his Audi RS6. The car had been purchased in January 2018 for £74,989 with a £7,500 deposit, the remainder financed. He later told the court the vehicle has been in Romania since early 2020. All of this appears in the Insolvency Service’s 3 December account of the case.

Alongside the car finance, the company entered two further hire purchase agreements in March 2018 covering seven items of plant valued at £84,829. Hrusca sold those machines for cash and, by his own account, gambled the proceeds, leaving the finance providers unpaid. The Insolvency Service summarised those facts in both its January sentencing note and its December confiscation update.

Corporate records show Vasile Hrusca Ltd entered creditors’ voluntary liquidation on 23 September 2019, with Christopher David Horner of Robson Scott Associates, 49 Duke Street, Darlington, appointed liquidator; the company was finally dissolved on 17 April 2025. The January sentencing note also records that Hrusca failed to deliver books and records to the liquidator-behaviour that typically frustrates asset tracing and increases costs for creditors.

For creditors reading this, the effect of a confiscation order matters. Under POCA, confiscation is a Crown debt designed to strip criminal benefit; it is not, by itself, a pot for distribution to suppliers, lenders or employees. Interest accrues on unpaid sums and a default prison term does not extinguish the liability. Courts can allow up to three months to pay (extendable to six months). These mechanics are set out in Crown Prosecution Service guidance and reflected in the Insolvency Service’s December release for this case.

Will any of the £190,577 reach the hire purchase banks or other creditors? The Insolvency Service’s public notices do not state that the court made a compensation order. Without such an order, money recovered under confiscation is paid to the state and then shared under the Home Office’s Asset Recovery Incentivisation Scheme; where compensation is ordered, it takes priority and is paid from sums enforced under the confiscation order. That hierarchy is described in CPS guidance.

The hire purchase position is straightforward for non‑lawyers: title typically remains with the finance company until the last payment is made. Selling the goods before that point amounts to theft. The Insolvency Service’s January summary explicitly noted that the machinery “belonged to the banks, not to his company until they were paid for in full”. That is precisely why lenders are the immediate victims when directors dispose of HP assets.

One unresolved point is the Audi. The December release records that it has been in Romania since early 2020, yet there is no reference to any restraint order having been sought before it left the UK. CPS guidance makes clear that restraint orders are available to freeze assets during investigations; whether one was pursued here is not stated in the public record. The gap matters because early restraint could have protected value for eventual recovery.

On sanction, Hrusca’s four‑year director ban sits within the lower bracket that courts typically reserve for less serious cases; the recognised bands in Sevenoaks run 2–5 years (lower), 6–10 (middle) and 11–15 (upper), and public guidance confirms the maximum at 15 years. Some creditors may question whether a four‑year term reflects the admitted asset sales and misuse of company money, but those bands are well established.

Next steps are time‑critical. Based on the order made on 25 November 2025, Hrusca must pay by 25 February 2026 unless the court extends the period. If he defaults, enforcement action can begin and the two‑and‑a‑half‑year default term can be activated while interest continues to run. For creditors, any commercial recovery still depends on civil claims, insurance or a compensation order, not on the confiscation alone.