In 2010 the Office of Fair Trading said unsecured creditors were routinely outgunned in corporate insolvencies and urged an independent complaints route with power to claw back overcharged fees. The watchdog also concluded that fee-setting worked better when secured creditors had skin in the game; once banks were repaid in full, the rest too often paid more and got less. That was the baseline. Fifteen years on, Inside Corporate Insolvency has gone back through laws, guidance and enforcement data to test what has really shifted for creditors.

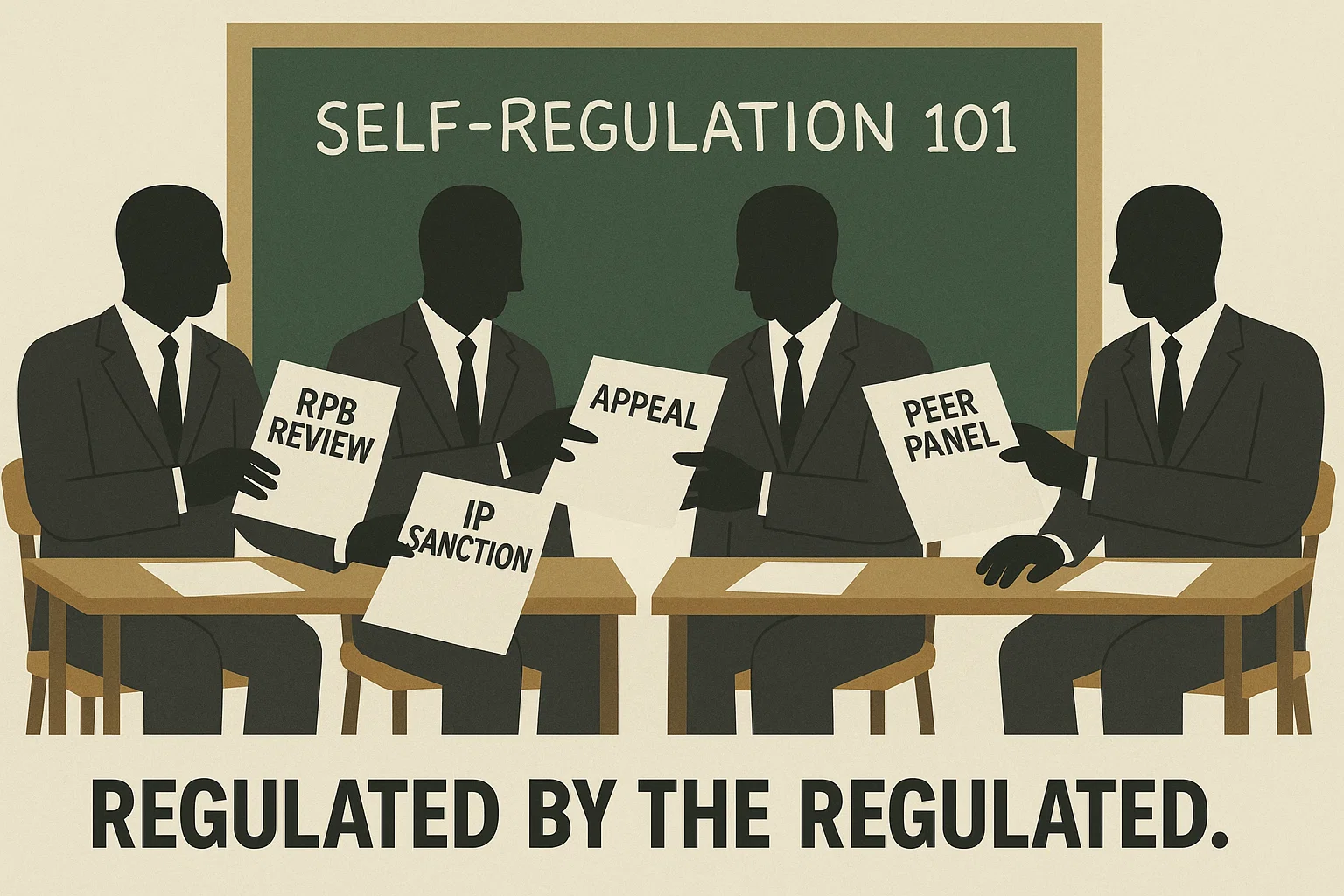

On structure, Britain still relies on self‑regulation. Insolvency practitioners are licensed by Recognised Professional Bodies (accountancy institutes and the IPA) while the Insolvency Service polices the regulators. Parliament did add teeth in the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015: statutory objectives for RPBs, a menu of sanctions against regulators, and a public‑interest power for the Secretary of State to ask the High Court for a direct sanctions order against an individual IP. But the model remains membership bodies regulating their own members, with government in oversight mode.

There has been some consolidation. Chartered Accountants Ireland has now exited from IP regulation entirely. From 1 June 2025 CAI ceased to be an RPB by statutory instrument, leaving three GB regulators: ICAEW, IPA and ICAS. The Insolvency Service’s latest annual review confirms that shift and shows around 1,500 authorised IPs at the start of 2025. Structural change, yes. A fundamentally different regulatory philosophy, no.

Complaints were centralised in 2013 through the Insolvency Service’s Complaints Gateway. The first‑year report showed a higher volume of complaints being captured. A decade on, throughput remains sizeable but the referral rate is falling: in 2024 the Gateway received 656 complaints; just 22% were referred to an RPB, 19% were rejected, 44% closed for want of information or contact, and 15% were awaiting information at year‑end. Only 1 of 39 appeals against rejection was upheld. That is process - but it is not redress.

Creditor redress remains the missing piece. The government’s own guidance is blunt: the complaints system doesn’t provide compensation. In theory, the 2015 Act’s “direct sanctions order” lets the Secretary of State ask the court to force an IP to contribute up to their fees to affected creditors, but the Insolvency Service’s annual reviews catalogue RPB sanctions rather than public applications for court‑ordered redress. If the power is being used, it is not visible in those summaries.

Fees and information are more regulated than in 2010. Since October 2015, office‑holders seeking to charge time costs must give creditors an upfront fee estimate (which operates as a cap unless varied by creditor approval) and set out likely work and expenses. SIP 9 was rewritten accordingly. That is genuine progress on transparency - though its value depends on creditors using the rights they now have.

At the same time, the 2016 Rules ripped out the default of in‑person creditors’ meetings, replacing them with decision procedures and “deemed consent”. Deemed consent cannot be used to approve remuneration, but the broader shift has undeniably reduced the number of occasions where creditors face an office‑holder across a table and press points on costs, investigations and strategy. That matters in small estates where every hour billed erodes any hope of a dividend.

Pre‑packs - the flashpoint of 2010 - are no longer purely a gentleman’s agreement. Since April 2021, any disposal in the first eight weeks of administration to a connected party requires either creditor approval or a “qualifying report” from an independent evaluator with insurance and no conflicts. That is a statutory trip‑wire, introduced after a decade of grumbling about voluntary codes.

But the connected‑party regime still leaves the buyer choosing - and paying - the evaluator, with no set professional qualification and the administrator free to proceed even after a negative opinion (albeit with reasons to creditors and Companies House). Practitioners and academics have warned about “shopping around” for friendlier reports. It is not hard to see why unsecured creditors remain sceptical.

The data fuels that unease. R3’s own magazine reported that pre‑packs rose from 201 in 2021 to 545 in 2023, with connected‑party sales more than tripling over the same period - and only one evaluator’s report in 2023 saying the case wasn’t made. That is not proof of a captured process, but it hardly screams robust challenge.

For a reminder of why independent scrutiny matters, recall the Miss Sixty litigation. In 2010 Henderson J set aside a CVA that stripped landlord guarantees, criticising the administrators’ approach; as one contemporary law‑firm note put it, the proposal “should never have seen the light of day”. The administrators were Peter Hollis and Nicholas O’Reilly (then of Vantis). Cases like that shaped today’s rhetoric on fairness - yet the safeguards still largely rely on professionals marking each other’s homework.

One area that clearly has moved is bonding. From 1 December 2024 the general penalty sum on IP bonds tripled to £750,000; bonds must now include run‑off cover of at least two years after release and set minimum indemnity periods for specific penalty sums, with SONIA‑linked interest on losses. Those changes matter when fraud or dishonesty drains an estate.

And what of outcomes for the people the system is meant to serve? Independent research commissioned by the Insolvency Service and published in its 2024 review found that in most CVLs realisable assets were very low: in 70% of cases researchers looked at, recoveries were below £10,000; in 14% they were nil. In that world, fees and expenses quickly consume what little there is and unsecured creditors rarely see a cheque.

Ministers flirted with scrapping self‑regulation altogether. After consulting on a single independent regulator, the government stepped back in September 2023. Instead it plans to regulate firms (not just individuals), create a public register that shows sanctions, and work up a compensation scheme for misconduct - when parliamentary time allows. The direction sounds right; the delivery timeline is vague.

So what has really changed since 2010? There is more paper: fee caps, longer bond cover, evaluator opinions, oversight reports and sanction lists. There are fewer regulators after CAI’s exit, and more formal levers in statute. But the system still asks membership bodies to police their own, while unsecured creditors largely fund the process without a practical route to get money back when conduct falls short. Until firm‑level regulation and a workable compensation scheme exist - and are used - scepticism will remain justified.

For creditors facing an appointment today, the rules can be made to work - but only if they are used. Push for clear, realistic fee estimates; insist on reasons where a connected‑party sale is waved through on a thin evaluator report; and, where necessary, force decisions onto a proper decision procedure or into court. The framework has evolved. The incentives haven’t. That is the gap policymakers still haven’t closed.